- Home

- Tiffany Reisz

The Chateau_An Erotic Thriller Page 9

The Chateau_An Erotic Thriller Read online

Page 9

Kingsley realizes he’s said this aloud when the boy laughs in his ear.

“You won’t think so after,” the boy says.

But Kingsley doesn’t retort. Why should he? This is what he’s wanted for seven long years. The boy is buried inside him, his movements deep and brutal. The pleasure is so sharp it’s almost agony. With every rough thrust, Kingsley tells the boy a secret.

I love you.

I still love you.

I hate you.

I still hate you.

I want you.

I’ll always want you.

I only left you so you’d come and find me.

Come and find me.

Find me and come.

“Shut the fuck up,” the boy says and Kingsley laughs. The boy clamps a hand over Kingsley’s mouth, silencing him.

Kingsley’s hands dig deep in the wet rare earth. The boy is insatiable. His teeth nip every inch of Kingsley’s back and shoulders. The boy’s other hand is clamped hard over Kingsley’s wrist. On the ground, in the dirt, they couple like wild animals—without mercy, without shame. The thrusts are vicious. The grunting bestial. If Kingsley dies from this, he will die happy.

When the boy fills him with a heated rush of semen, Kingsley comes hard enough he sees only white again and the forest is filled with his cries.

It is over now and Kingsley is empty.

“Again,” Kingsley begs.

The boy laughs in his ear. “Now I’ll kill you,” he says.

Kingsley almost laughs. This is something the boy would say.

“How?” Kingsley asks.

“Like this.”

And then the boy is gone.

15

When Kingsley woke from his dream, it was still full night. Polly lay next to him in the bed on her side and soundly sleeping. He wanted to wake her, to hear a human voice give him words of comfort. He would have given his right arm for a woman’s gentle hand on his forehead and a woman’s gentle voice whispering, “It’s all right… It was just a dream.”

Only a dream, he told himself. Nothing more. Even as Kingsley rolled up into a sitting position, his fear of the wolf and the dream were already fading. The pain was gone. The ecstasy, too. It was all gone.

Except the loneliness, the terrible loneliness. That remained.

Two unpleasant urges pulled him from the warmth of Polly’s bed. He went to the bathroom to relieve the first, more pressing one. He washed his face in the sink, drank fistfuls of cold water, and found his jeans where he’d dropped them. He didn’t know the rules about smoking in the château, so, after dressing, he snuck past the bed and went out onto the balcony, closing the door as quietly as possible behind him.

Before he and Polly had gone to bed together, the moon had been high and white. Now it was hidden behind thick clouds. The night air was brisk, and he lit up quickly, not wanting to stay out in the cold any longer than he had to. He should have put on his shoes, he realized. Shirtless and shoeless, he started shivering by the third drag. But he didn’t rush. He liked the cold, even if he didn’t like to think about why. He stood on the balcony, hips against the iron railing and inhaled deep of the January night air. It tingled his nose like mint and tasted sweet as a frozen strawberry on his tongue. This was one of those rare winter nights when it seemed winter would last forever.

Snow was coming.

Madame had mentioned that it might snow. And Polly, too, seemed eager for it. Why they wanted it to snow, he couldn’t say, but he knew why he wanted the snow, and he wished he didn’t. Snow was his enemy. It made it so much harder if he had to escape on foot.

Kingsley stubbed his cigarette out in the dead potted plant on the balcony. He turned to go back inside when he heard a sound.

A soft, plaintive cry.

A baby’s cry.

Jacques.

The balcony stretched for the entire length of the second floor. Kingsley ran down to the nursery and found the balcony door unlocked. He slipped inside and shut the door behind him quickly so Jacques wouldn’t feel the cold draft. He went to the cradle. The baby boy was screaming so hard he was shaking, his two little fists balled up so tiny and tight, Kingsley couldn’t help but laugh.

He wasn’t sure what to do. He hadn’t even held a small child since he was, what, fourteen? Some cousin of his father’s had stopped by with her little girl. Surely someone in the house would be coming to see to Jacques to change his diaper or feed him. Meanwhile, the poor boy was bleating his head off.

“Shh…” Kingsley said, and laid his hand over the top of Jacques’s small head. “You’ll wake the whole house.”

The touch seemed to startle Jacques into silence. The baby’s eyes went wide and rolled about as if trying to see who this strange person was who’d dared touch the royal baby head.

“There you go,” Kingsley said. “That’s better. We’re Frenchmen, you and me. We don’t fuss like that. We leave that to American boys, right?”

Jacques didn’t answer, but at least he didn’t take up screaming again.

“How old are you?” Kingsley asked as he stroked Jacques’s little head. His skin was soft and his hair fluffy and fine as down. “I’m twenty-four. Twenty-four years, I mean. What are you? Twenty-four days?”

“He’s six weeks old.”

Kingsley looked up and saw Madame coming into the nursery. She held a glass baby bottle in her hand.

“I’m sorry,” Kingsley said at once. “I heard him cry when I was on the balcony and I just—”

“You’ve done nothing wrong,” she said, waving her hand, dismissing his apologies. “Would you like to feed him?”

“Me?” Kingsley said.

“Go on. I know you want to. No man who hates children would run into a screaming baby’s nursery. They tend to run in the opposite direction very fast.”

“No, I like children,” Kingsley said. “I don’t really know what to do with a small baby though.”

“Only one way to learn. Pick him up carefully, cradle his head. Don’t let it fall back…”

Kingsley took a steadying breath and then as gently as he could he scooped Jacques out of the crib with both of his hands under the boy. “This is not what I expected to be doing tonight,” he said, bringing the baby to his shoulder. He instinctively bounced him a couple times while patting his back.

“What had you planned on doing tonight?” Madame asked. “Before you came to the château, I mean?”

She helped Kingsley put Jacques on his back into the correct feeding position. Though he wouldn’t say it out loud, he thought Madame looked quite cute in her pajamas. They were gray silk, embroidered with white-and-black flowers and a mandarin collar. She had such a quiet power about her, even in her nightclothes, that Kingsley had trouble picturing her as any man’s submissive. Apparently neither could she.

“I’ve been on medical leave,” Kingsley said as he settled Jacques’s head against his bicep. “So I do nothing. Not nothing. Every night I go out, drink too much, find a girl, and bring her back to my place.”

“Sounds dull.” Madame handed him the bottle. It felt warm in his hand, but not too warm. “You don’t seem like a dull person to me.”

He shrugged. “It’s my cover.”

“Here,” she said and took the bottle from him again. “Bring it to his lips but don’t push it in. When he feels it’s a nipple, he’ll start suckling.”

“Typical male,” he said.

Jacques did exactly what Madame predicted. Once the bottle was at his mouth, he latched onto it. Kingsley grinned. Amazing.

“When you grow up,” Kingsley said to Jacques, “eating and sucking nipples are two entirely different pleasures.”

Madame smiled, and the hard lines of her mouth softened. “Jacques is our first boy in twenty-five years,” she said. “We tend to breed mostly girls.”

“Where is he now?” Kingsley asked. “Your last boy?”

“Paris,” she said. “Working. But like our girls, he’s still drawn

back to us. He visits me often, brings me all the gossip. The children of this house are all very loyal even if their parents are not. If you’re not careful, you’ll end up falling in love with this place.”

“I’m not careful,” Kingsley said. “I might come back just to visit him.” He looked down at little Jacques who was happily eating away, his tiny fists dancing around his head in pleasure.

“A good boy,” Madame said, approvingly.

“He is,” Kingsley said.

“I meant you,” she said.

Kingsley smiled as he adjusted Jacques’s position on his bicep.

“Does his mother not feed him?” Kingsley asked.

“That isn’t the concern of any of the men of this household.”

“Sorry. You’re right, it isn’t.”

“Curiosity is human. If you must know, his mother had a very hard delivery. She lost blood. For a week after, she could barely take care of herself, much less him. No nursing. Doctor’s orders. Nursing a child takes a lot out of a woman, and she needed all her strength for herself. Now she’s under my orders to sleep a full night, every night. She has us to care for her little boy from dusk until dawn.”

“It’s good she had you all then,” Kingsley said.

“People are meant to be together,” Madame said, pressing a quick and tender kiss on top of Jacques’s head. “I would go mad if I had to live alone.”

“It’s not so bad,” Kingsley said.

“If you like being alone, why do you bring a girl home with you every single night? Hmm?”

Kingsley nodded. “Maybe you’re right. Maybe.”

“I am,” she said. “But I won’t belabor the point. Did Jacques’s crying wake you up? I would have thought Polly had worn you out by now.”

“She tried,” he said, and smiled. The smiled faded. “I had another dream.”

“Ah,” she said.

Madame only gave him a pointed look as she placed a white cloth over his shoulder.

“You’ll have to burp him,” she said. “Or I can.”

“I’ll do it. I think,” Kingsley said. “Do I…”

“Here.” Madame helped Kingsley position little Jacques against his shoulder and then Madame patted the baby firmly on the back, twice. Jacques made a little noise, like a hiccup but wetter.

“Is that it?” Kingsley asked.

Madame wiped off Jacque’s tiny mouth. “All done. And he’s a very happy boy now. But leave him there. He seems comfortable. So do you.”

Kingsley felt comfortable and was glad he didn’t have to put the boy down yet. Madame sat in the large rocking chair by the white cradle, and Kingsley paced the floor as Jacques wriggled and rooted around in his arms until he settled down again. When he could safely turn his back on Madame, Kingsley quickly lowered his nose to the baby’s head and inhaled the scent of talc and lavender. The scent of innocence.

“See?” she said. “It’s not so hard. You’ll make a good father someday.”

“Polly said you don’t know who Jacques’s father is?”

“It could be any of the men in the house. In time he may show a resemblance, but it really doesn’t matter.” Her tone was light, her expression indifferent. She truly couldn’t care less who’d sired the boy.

Kingsley shook his head. “That would be torture, not knowing if he was mine or not.”

“If you lived in this house,” she said, “he would be yours. He’s all of ours.”

“Still,” Kingsley said. “I would need to know.”

“That’s not our way,” she said, and she said as if that ended the discussion. But then she smiled again, her face softened. “He likes you. Usually he’s fussy with men.”

“Hard to believe we were all this little once. He seems so…defenseless.”

“That’s what he has us for,” she said. “We protect the defenseless here.”

“Do you? You don’t know me from Adam, and you let me in your house and into the baby’s room?”

Madame sat back in the rocking chair, crossed her legs at the ankles, and rocked slowly. “Kingsley Théophile Boissonneault. Age twenty-four. Birthday November second. After your parents died when you were fifteen, you had to move to Maine in America to live with your maternal grandparents. After the death of your sister while she was visiting you at the St. Ignatius Catholic School for Boys, you accompanied her body to France to be buried. You joined la Légion at seventeen. You work for an unnamed agency under the umbrella of the French Armed Forces that does ‘special assignments,’ which is a euphemism, I think, that means you kill people. You went through officer training two years ago. After a successful mission in the Swiss Alps two months ago, you were promoted to first lieutenant. You were also injured during the mission—two broken ribs that seem to have healed very nicely—but otherwise you have been given a clean bill of health, physically and psychologically.”

Kingsley only stared at her a good long while.

Madame kept rocking. “Do you think I would let just anyone into my home? Near my family? Near me?” She pointed her hand at Jacques in a graceful gesture. “Near him?”

“How do you—”

“I have friends in interesting places,” she said.

“Dangerous places,” Kingsley said. “The colonel is a very dangerous man. If you have someone near him, feeding you information, get him out now. For his sake. For yours.”

“Your concern is very touching,” Madame said. “We’ll all be fine, I promise.”

“You knew who I was before I even called.”

“I’m glad you didn’t lie to me too much. I would have known. I like lying, but I don’t like being lied to.”

Kingsley could think of nothing to say. She’d stunned him into silence, which, like making him feel shy, was quite an accomplishment.

“Is that everything there is to know about you?” Madame asked.

“Yes,” he breathed.

“Are you certain of that?”

“I think. What else is there to know?”

She returned to rocking again. Kingsley returned to pacing the floor with Jacques. Then she said something that might have caused him to drop the baby if he hadn’t been so well-trained.

“Kingsley, who is Marcus Stearns?”

16

By the time she’d asked that question, he’d managed to put his mask back on. His cavalier mask. His mask of indifference.

“Marcus Stearns was my sister’s husband,” Kingsley said. “A teacher at the school I went to in Maine. A student and then a teacher.”

“But he was more than that, yes?”

Kingsley didn’t answer. He simply patted Jacques on the back again, and caressed the baby’s soft warm cheek.

“Ah, so he was,” she said. “In your personnel file, he’s listed as your next of kin. The person to contact in event of your death. An important position in your life.”

Kingsley said nothing.

“Put Jacques in his crib,” Madame said.

He stared hard at her. He didn’t want to let go, and she knew it.

She smiled a wicked smile. “If you want to hold him, you will answer my questions. If you don’t want to, you must put him down.”

“You’ll use a baby as a weapon?” Kingsley asked. “You are a sadist.”

“You want to hold Jacques. I want answers. Either put him down or answer my questions.”

Kingsley took a deep breath. Little Jacques’s hand latched onto Kingsley’s collarbone, the fingernails digging into his skin like five tender needles.

“Why is Marcus Stearns listed as the next of kin in your files?” Madame asked.

“He was married to my sister.”

“Your sister who is dead. He’s not family to you anymore.”

“I have no one else,” he said. “It was either him or a couple of my father’s cousins I haven’t seen in years.”

“He was the one you served, wasn’t he?” Madame asked. “The angel. The demon. The monster. I imagined it was a priest

at your school when you told me. I thought he was someone much older, someone with power over you. But no. He was just a boy.”

“He was not ‘just’ anything,” Kingsley said.

“Ah, so I’m right,” she said. “Your master married your sister. And you call me a sadist?”

Kingsley said nothing again. He didn’t trust his own voice.

“Funny. I say ‘sister’ and nothing happens to your eyes,” Madame said. “I mention him, and I see lightning, thunder.” She waved a hand over her face to mimic a storm.

“Maybe I want to throw lightning at him,” Kingsley said.

“That’s passion,” she said. “You must still love him.”

“I hate him. I’d kill him if I saw him again.”

“I could say the same for my husband,” she said.

Again, Kingsley said nothing.

“Put Jacques down in his cradle if you won’t talk,” she said. “Those are the rules.”

Kingsley wasn’t ready to relinquish the little boy yet. He’d forgotten how solid babies were. Even when tiny, they had heft to them. They weighed somehow more than their actual weight. Was it life that gave them that weight? Was it the weight of the soul he felt? The whole of the tree fit inside a single seed. Did the whole of a man’s life live inside this tiny form Kingsley could cradle against his shoulder?

“What do you want to know about him?” Kingsley asked.

“Everything,” Madame said.

“Everything. All right. I’ll tell you everything. He’s beautiful,” Kingsley said. “You’ve never seen anyone more beautiful than him. Before him, I never loved a boy. Never even thought of it. I loved girls. I’d had my first when I was twelve, thirteen? Fifty by the time I was sixteen. Then I saw him.”

Kingsley closed his eyes as if he could hide from the memory. The memory found him anyway.

He continued, “His hair is like spun gold. His eyes are the color of a January sky before it snows. He even smells…he smells just like winter. He’s smart. Too smart. There’s an American phrase for when they want to say someone is stupid. They say, ‘He’s not the sharpest knife in the drawer.’ ”

Madame smiled.

The Bourbon Thief

The Bourbon Thief The Saint

The Saint The Siren

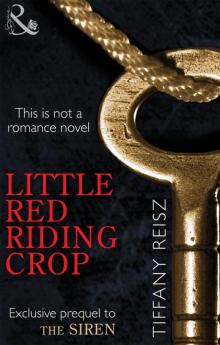

The Siren Little Red Riding Crop

Little Red Riding Crop Her Halloween Treat

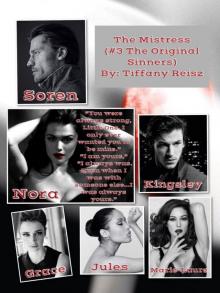

Her Halloween Treat The Mistress

The Mistress The Last Good Knight

The Last Good Knight The Gift (Seven Day Loan)

The Gift (Seven Day Loan) The Queen

The Queen The Angel

The Angel The Prince

The Prince Misbehaving

Misbehaving The Red

The Red Submit to Desire

Submit to Desire The Priest: An Original Sinners Novel

The Priest: An Original Sinners Novel The Lucky Ones

The Lucky Ones The Mistress Files

The Mistress Files Mischief

Mischief The King

The King The Night Mark

The Night Mark The Virgin

The Virgin Her Naughty Holiday

Her Naughty Holiday One Hot December

One Hot December The Auction (The Original Sinners Pulp Library)

The Auction (The Original Sinners Pulp Library) A Winter Symphony: A Christmas Novella

A Winter Symphony: A Christmas Novella The Pearl (The Godwicks)

The Pearl (The Godwicks) Immersed In Pleasure/Submit To Desire (The Original Sinners Pulp Library)

Immersed In Pleasure/Submit To Desire (The Original Sinners Pulp Library) The Rose

The Rose Winter Tales: An Original Sinners Christmas Anthology

Winter Tales: An Original Sinners Christmas Anthology Winter Tales

Winter Tales The Last Good Knight (The Original Sinners Pulp Library)

The Last Good Knight (The Original Sinners Pulp Library) The Return (The Original Sinners)

The Return (The Original Sinners) 0778318435 (A)

0778318435 (A) Seven Day Loan

Seven Day Loan Picture Perfect Cowboy

Picture Perfect Cowboy The Christmas Truce

The Christmas Truce 10 Shades of Seduction

10 Shades of Seduction The Chateau_An Erotic Thriller

The Chateau_An Erotic Thriller The Christmas Truce: An Original Sinners Novella

The Christmas Truce: An Original Sinners Novella Immersed in Pleasure

Immersed in Pleasure Harlequin E Shivers Box Set Volume 4: The HeadmasterDarkness UnchainedForget Me NotQueen of Stone

Harlequin E Shivers Box Set Volume 4: The HeadmasterDarkness UnchainedForget Me NotQueen of Stone Something Nice: An Original Sinners Novella

Something Nice: An Original Sinners Novella The Confessions

The Confessions The Mistress Files: The Case of the Acting ActressThe Case of the Diffident DomThe Case of the Reluctant Rock StarThe Case of the Secret SwitchThe Case of the Brokenhearted Bartender

The Mistress Files: The Case of the Acting ActressThe Case of the Diffident DomThe Case of the Reluctant Rock StarThe Case of the Secret SwitchThe Case of the Brokenhearted Bartender One Hot December (Mills & Boon Blaze) (Men at Work, Book 3)

One Hot December (Mills & Boon Blaze) (Men at Work, Book 3) The Scent of Winter: A Novella

The Scent of Winter: A Novella Little Red Riding Crop (Spice) (Prequel to The Siren: Book 1 in The Original Sinners series)

Little Red Riding Crop (Spice) (Prequel to The Siren: Book 1 in The Original Sinners series)