- Home

- Tiffany Reisz

The Prince

The Prince Read online

Page 1

Author: Tiffany Reisz Prologue

File #1312—From the archives

SUTHERLIN, NORA

Née Eleanor Louise Schreiber

Born on March 15, 1977 (beware the Ides of March)

Father: William Gregory Schreiber, deceased (you’re welcome, ma cherie), formerly incarcerated in Attica on multiple counts of grand theft auto, and possession of stolen property. Had connections with organized crime—see file #1382.

Mother: Margaret Delores Schreiber, née Kohl, age fifty-six, currently residing near Guildford, New York, at the Sisters of Saint Monica convent (cloistered), known now as Sister Mary John.

Daughter and mother—estranged but currently in détente.

Age 15, Eleanor met Father Marcus Lennox Stearns (Søren, born to Gisela Magnussen). After her arrest for stealing five luxury vehicles in one night to aid her father in paying off a debt, Sutherlin was sentenced to probation and twelve hundred hours of community service supervised by Father Stearns. It was during these years that Sutherlin learned to submit. At age eighteen she became his collared submissive. At age twenty-eight she left him after terminating a pregnancy (father—me). For a year she lived with her mother at the convent upstate, before returning to the city and becoming a dominatrix in the employ of the devastatingly handsome Kingsley Edge, Edge Enterprises. At the time of this filing she has had five books published, four of which have been bestsellers. (See attached for financials. Her editor is Zachary Easton, publisher Royal House. See file #2112, drawer seven for Easton’s file. ) At age thirty-three, after spending five years apart, she returned to her owner and has been with him ever since.

Sexual preferences—Sutherlin is bisexual although she generally shows a preference for men. A true switch, she tends to top with anyone but her owner (because, as we all know, he would break her if she tried).

Weaknesses—Blondes—men and women, younger men, tiramisu.

Ultimate weakness—Unknown. Possibly John Wesley Railey, born September 19, Versailles, Kentucky. Heir to the Railey Fortune (estimated at $930 million as of 2010) and The Rails Farm (Thoroughbreds, saddlebreds), Railey, known to friends and family as Wes or Wesley, lived with Sutherlin from January 2008 until April 2009. As the sole heir to the largest horse farm in the world, Wesley is known colloquially as the Prince of Kentucky. Six feet tall, a type 1 diabetic, boyishly handsome, not sexually active at the time of his filing (Railey file #561, drawer 4). Sutherlin has displayed intense emotion, affection and loyalty (and possibly even love) where Railey is concerned.

Strengths—Extremely intelligent, IQ 167, physically strong, cunning, highly manipulative when necessary, extremely beautiful (see attached photographs), Sutherlin is far more dangerous than she appears.

The final line in the file the thief read over and over again.

In all things involving Nora Sutherlin, proceed with caution.

Three months…for three long and sleepless months, the thief toiled over the file, which had been encrypted in layer upon layer of cipher. The thief knew French and Haitian Creole, but merely knowing the languages wouldn’t crack the code. One had to know Kingsley Edge, and luckily, the thief did—intimately.

The file thief read through all four pages of notes on Nora Sutherlin a thousand times until the words were as familiar as the thief’s own name. And as the thief read the pages until they grew tattered from wear, an idea began to form and grow until it gave birth to a plan.

The thief closed the file for the final time, and then and there decided the best course of action.

The thief would proceed…cautiously.

NORTH

The Past

They’d sent him here to save his life.

At least that was the line his grandparents laid on him to explain why they’d decided to take him out of public school and send him instead to an all-boys Jesuit boarding school nestled in some of the most godforsaken terrain on the Maine-Canadian border.

They should have let him die.

Hoisting his duffel bag onto his shoulder, he picked up his battered brown leather suitcase and headed toward what appeared to be the main building on the isolated campus. Everywhere he looked he saw churches, or at least buildings with pretensions of being one. A cross adorned every roof. Gothic iron bars grated every window. He’d been wrenched from civilization and dropped without apology in the middle of a medieval monk’s wet dream.

He entered the building through a set of iron-and-wood doors, the ancient hinges of which screamed as if being tortured. He could sympathize. He rather felt like screaming himself. A fireplace piled high with logs cast light and warmth into the dismal gray foyer. Huddling close to it, he wrapped his arms about himself, wincing as he did so. His left wrist still ached from the beating he’d taken three weeks ago, the beating that had convinced his grandparents that he’d be safe only at an all-boys school.

“So this is our Frenchman?” The jovial voice came from behind him. He turned and saw a squat man all in black beaming from ear to ear. Not all black, he noted. Not quite. The man wore a white collar around his neck. The priest held out his hand to him, but he paused before shaking it. Celibacy seemed like a disease to him—one that might be catching. “Welcome to Saint Ignatius. Come inside my office. This way. ”

He gave the priest a blank look, but followed nonetheless.

Inside the office, he took the chair closest to the fireplace, while the priest sat behind a wide oak desk.

“I’m Father Henry, by the way,” the priest began. “Monsignor here. I hear you’ve had some trouble at your old school. Something about a fight…some boys taking exception to your behavior with their girlfriends?”

Saying nothing, he merely blinked and shrugged.

“Good Lord. They told me you could speak some English. ” Father Henry sighed. “I suppose by ‘some’ they meant ‘none. ’ Anglais?”

He shook his head. “Je ne parle pas l’anglais. ”

Father Henry sighed again.

“French. Of course. You would have to be French, wouldn’t you? Not Italian. Not German. I could even handle a little ancient Greek. And poor Father Pierre dead for six months. Ah, c’est la vie,” he said, and then laughed at his own joke. “Nothing for it. We’ll make do. ” Father Henry rested both his chins on his hand and stared into the fireplace, clearly deep in deliberation.

He joined the priest in his staring. The heat from the fireplace seeped through his clothes, through his chilled skin and into the core of him. He wanted to sleep for days, for years even. Maybe when he woke up he would be a grown man and no one could send him away again. The day would come when he would take orders from no one, and that would be the best day of his life.

A soft knock on the door jarred him from his musings.

A boy about twelve years old, with dark red hair, entered, wearing the school uniform of black trousers, black vest, black jacket and tie, with a crisp white shirt underneath.

All his life he had taken great pride in his clothes, every detail of them, down to the shoes he wore. Now he, too, would be forced into the same dull attire as every other boy in this miserable place. He’d read a little Dante his last year at his lycée in Paris. If he remembered correctly, the centermost circle of hell was all ice. He glanced out the window in Father Henry’s office. New snow had started to fall on the ice-packed ground. Perhaps his grandfather had been right about him. Perhaps he was a sinner. That would explain why, still alive and only sixteen years old, he’d been sent to hell on earth.

“Matthew, thank you. Come in, please. ” Father Henry motioned the boy into the office. The boy, Matthew, cast curious glances at him while standing at near attention in front of the priest’s de

sk. “How much French did you have with Father Pierre before he passed?”

Matthew shifted his weight nervously from foot to foot. “Un…année?”

Father Henry smiled kindly. “It’s not a quiz, Matthew. Just a question. You can speak English. ”

The boy sighed audibly with relief.

“One year, Father. And I wasn’t very good at it. ”

“Matthew, this is Kingsley…” Father Henry paused and glanced down at a file in front of him “…Boissonneault?”

Kingsley repeated his last name, trying not to grimace at how horribly Father Henry had butchered it. Stupid Americans.

“Yes, Kingsley Boissonneault. He’s our new student. From Portland. ”

It took all of Kingsley’s self-control not to correct Father Henry and remind him that he’d been living in Portland for only six months. Paris. Not Portland. He was from Paris. But to say that would be to reveal he not only understood English, but that he spoke it perfectly; he had no intention of gracing this horrible hellhole with a single word of his English.

Matthew gave him an apprehensive smile. Kingsley didn’t smile back.

“Well, Matthew, if your French is twice as good as mine, we’re out of options. ” Father Henry lost his grin for the first time in their whole conversation. Suddenly he seemed tense, concerned, as nervous as young Matthew. “You’ll just have to go to Mr. Stearns and ask him to come here. ”

At the mention of Mr. Stearns, Matthew’s eyes widened so hugely they nearly eclipsed his face. Kingsley almost laughed at the sight. But when Father Henry didn’t seem to find the boy’s look of fear equally funny, Kingsley started to grow concerned himself.

“Do I have to?”

Father Henry exhaled heavily. “He’s not going to bite you,” the priest said, but didn’t sound quite convinced of that.

“But…” Matthew began “…it’s 4:27. ”

Father Henry winced.

“It is, isn’t it? Well, we can’t interrupt the music of the spheres, can we? Then I suppose you’ll just have to make do. Perhaps we can persuade Mr. Stearns into talking to our new student later. Show Kingsley around. Do your best. ”

Matthew nodded and motioned for him to follow. In the foyer they paused as the boy wrapped a scarf around his neck and shoved his hands into gloves. Then, glancing around, he curled up his nose in concentration.

“I don’t know the French word for foyer. ”

Kingsley repressed a smile. The French for “foyer” was foyer.

Outside in the snow, Matthew turned and faced the building they’d just left. “This is where all the Fathers have their offices. Le pères…bureau?”

“Bureaux, oui,” Kingsley repeated, and Matthew beamed, clearly pleased to have elicited any kind of encouragement or understanding from him.

Kingsley followed the younger boy into the library, where Matthew desperately sought out the French word for the place, apparently not realizing that the rows upon rows of bookcases spoke for themselves.

“Library…” Matthew said. “Trois…” Clearly, he wanted to explain that the building stood three stories high. He didn’t know the word for stories any more than he knew library, so instead he stacked his hands on top of each other. Kingsley nodded as if he understood, although it actually appeared as if Matthew was describing a particularly large sandwich.

A few students in armchairs studied Kingsley with unconcealed interest. His grandfather had said only forty or fifty students resided at Saint Ignatius. Some were the sons of wealthy Catholic families who wanted a traditional Jesuit education, while the rest were troubled young men the court ordered here to undergo reformation. In their school uniforms, with their similar shaggy haircuts, Kingsley couldn’t tell the fortunate sons from the wards of the court.

Matthew led him from the library. The next building over was the church, and the boy paused on the threshold before reaching out for the door handle. Raising his fingers to his lips, he mimed the universal sign for silence. Then, as carefully as if it were made of glass, he opened the door and slipped inside. Kingsley’s ears perked up immediately as he heard the sound of a piano being played with unmistakable virtuosity.

The Bourbon Thief

The Bourbon Thief The Saint

The Saint The Siren

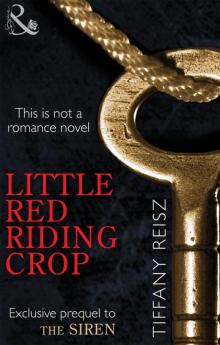

The Siren Little Red Riding Crop

Little Red Riding Crop Her Halloween Treat

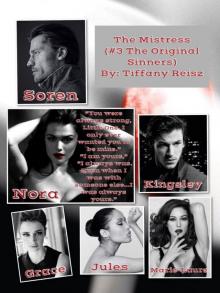

Her Halloween Treat The Mistress

The Mistress The Last Good Knight

The Last Good Knight The Gift (Seven Day Loan)

The Gift (Seven Day Loan) The Queen

The Queen The Angel

The Angel The Prince

The Prince Misbehaving

Misbehaving The Red

The Red Submit to Desire

Submit to Desire The Priest: An Original Sinners Novel

The Priest: An Original Sinners Novel The Lucky Ones

The Lucky Ones The Mistress Files

The Mistress Files Mischief

Mischief The King

The King The Night Mark

The Night Mark The Virgin

The Virgin Her Naughty Holiday

Her Naughty Holiday One Hot December

One Hot December The Auction (The Original Sinners Pulp Library)

The Auction (The Original Sinners Pulp Library) A Winter Symphony: A Christmas Novella

A Winter Symphony: A Christmas Novella The Pearl (The Godwicks)

The Pearl (The Godwicks) Immersed In Pleasure/Submit To Desire (The Original Sinners Pulp Library)

Immersed In Pleasure/Submit To Desire (The Original Sinners Pulp Library) The Rose

The Rose Winter Tales: An Original Sinners Christmas Anthology

Winter Tales: An Original Sinners Christmas Anthology Winter Tales

Winter Tales The Last Good Knight (The Original Sinners Pulp Library)

The Last Good Knight (The Original Sinners Pulp Library) The Return (The Original Sinners)

The Return (The Original Sinners) 0778318435 (A)

0778318435 (A) Seven Day Loan

Seven Day Loan Picture Perfect Cowboy

Picture Perfect Cowboy The Christmas Truce

The Christmas Truce 10 Shades of Seduction

10 Shades of Seduction The Chateau_An Erotic Thriller

The Chateau_An Erotic Thriller The Christmas Truce: An Original Sinners Novella

The Christmas Truce: An Original Sinners Novella Immersed in Pleasure

Immersed in Pleasure Harlequin E Shivers Box Set Volume 4: The HeadmasterDarkness UnchainedForget Me NotQueen of Stone

Harlequin E Shivers Box Set Volume 4: The HeadmasterDarkness UnchainedForget Me NotQueen of Stone Something Nice: An Original Sinners Novella

Something Nice: An Original Sinners Novella The Confessions

The Confessions The Mistress Files: The Case of the Acting ActressThe Case of the Diffident DomThe Case of the Reluctant Rock StarThe Case of the Secret SwitchThe Case of the Brokenhearted Bartender

The Mistress Files: The Case of the Acting ActressThe Case of the Diffident DomThe Case of the Reluctant Rock StarThe Case of the Secret SwitchThe Case of the Brokenhearted Bartender One Hot December (Mills & Boon Blaze) (Men at Work, Book 3)

One Hot December (Mills & Boon Blaze) (Men at Work, Book 3) The Scent of Winter: A Novella

The Scent of Winter: A Novella Little Red Riding Crop (Spice) (Prequel to The Siren: Book 1 in The Original Sinners series)

Little Red Riding Crop (Spice) (Prequel to The Siren: Book 1 in The Original Sinners series)