- Home

- Tiffany Reisz

The Bourbon Thief Page 8

The Bourbon Thief Read online

Page 8

up with.

It’s high time you earn your place in this family. Your mother thinks you’re getting a bit too big for your britches. She told me to take you down a peg or two.

This was why Momma left and didn’t come back. This was why. Because her mother had sold her, sold her out to her own grandfather. Sold her body to him in exchange for Red Thread. Her mother...that coward, that bitch, had driven away, leaving her alone with him so she didn’t have to hear her daughter’s screams. And her grandfather, this vile piece of shit, was going to rape her until she was knocked up and he could marry her off. He wanted a baby boy so bad he was going to make her have it for him. He would fuck her until she gave him one. If the first baby was a girl, he’d fuck her again and again and again. All for his dirty kingdom. If she could, she’d burn to the ground, right here and right now. She wanted fire, fire everywhere. She wanted her grandfather burning in hell and her mother burning right next to him and the house burning down, taking all of Red Thread with it.

Tamara pushed against her grandfather’s chest as hard as she could. Then she saw something.

A brown pool of water crept in under the door. She noticed it first. Her grandfather was too preoccupied undoing his pants to notice anything. But when he turned his head, he saw it, too.

“What the hell?” he said, his brow furrowed in frustration and confusion. For one second he looked the other way. For one second his mind wasn’t on her and what he was doing. For one second the water rapidly rushing into the room was more important than anything, even this.

That one second was all Tamara needed.

With her free hand she grabbed the lamp off the nightstand and smashed it against his head. He screamed and blood burst from his temple. In a daze he slumped onto his side, his hand over the bleeding wound, swearing and blinking, and Tamara wriggled her way out from under his bulk. Frantically she looked around for a weapon—anything would do—and saw a heavy silver candlestick on top of the dresser. Two inches of water surrounded her ankles as she stood up off the bed. Two inches and rising fast. The candlestick was heavy and square—art deco, a gift from her grandmother—and when she slammed it down onto her granddaddy’s head, it made a soft and awful thudding sound. He keeled over, not moving, not a muscle.

A gust of wind brushed across her body, lifting her hair. Ice-cold wind like someone had left the door open to winter and called it inside.

Tamara stood there and giggled a little. She’d gone to a slumber party two weeks ago and they’d played Clue. Miss Scarlet in the bedroom with the candlestick...

Noises came from the side of the house, jarring her from her delirium—something falling over, something else cracking and wood splintering like a door coming off the hinges. The water in the house was a foot high now, muddy and stinking and ice-cold. The shattered remains of the lamp covered the bed like glitter. In the window seat sat the bottle of Red Thread. Tamara picked it up and smashed it against the wall. The red ribbon around its neck fell into the water. She fished it out and grabbed her grandfather’s hand, twisting the ribbon around his index finger. He moaned and Tamara gasped. The water reached her knees.

Tamara grasped her grandfather by the ankles and dragged him off the bed. She couldn’t get any traction at first, but terror gave her strength. She tugged and lugged and pulled. His penis hung out of his unzipped pants like a fat earthworm. If she had garden shears handy, she would cut it off his body.

With one final yank on his belt loops, Tamara heaved him off the bed into the cold dirty water. And then, because she knew she had no other choice if she wanted to survive this night, she grabbed two fistfuls of his Lee Majors hair and shoved his head under the water.

Some part of his brain must have registered what was happening to him. He thrashed hard after the first inhale of muck, but she had the advantage now and wasn’t going to lose it. She held him down until he stopped moving and, to be on the safe side, long after he stopped moving.

When it was done, she stood there looking at him there in the water, floating, seaworthy as a garbage bag. He didn’t look like a person anymore.

From the other room came a screeching sound—the river rearranging the furniture. Tamara ripped the silky pink cover off her bed and shook the broken glass out of it. Wrapping it around herself like a shawl, she waded through the now knee-deep water to the door. The house had gone mad. Chairs floated. Papers and books bobbed on the surface like toy boats. The smell of sewage permeated the air. Somewhere a light flickered and Tamara had a new fear then—electrocution. She heard a squeak and saw movement in the water—a gray rat swimming down the hall to save itself. Panicking, Tamara forced her way past a china cabinet now turned on its side and floating and made it to the stairs. She rushed upstairs to the bathroom and hit her knees in front of the toilet. For what felt like an hour she wretched and vomited. She threw up so hard her throat tore and she urinated on herself. She could taste blood in her mouth.

Then the lights went out.

Tamara blinked, letting her eyes adjust to the dark. With the pink blanket around her again, she dragged herself to her feet and felt her way down the hall to her grandfather’s office. It faced the highway instead of the river. If the water kept rising, it would be the last room to flood. The door wasn’t locked, and if it had been, she would have busted the door down for the pleasure of breaking something. Inside the office she saw a black box on the desk. In the dark the telephone looked like a cat curled up and sleeping. Should she call for help? She didn’t know. She’d been warned once not to touch the telephone in a storm, but it wasn’t lightning. Carefully she picked up the receiver. The line was dead. She was all alone in the house with her grandfather’s dead body.

Tamara went to the window. The lawn was gone. The manicured horse pastures crisscrossed with white board fences—gone. Cobblestone driveway—gone. The stone fence built long before the Civil War by slave labor—gone. Now there was only water. Water water everywhere. Only the stable up on a high knoll had been spared. If the water kept rising, it would be the next to go. And so would she.

When she was a little girl in Sunday school, she had learned the story of Noah and his ark. From what she remembered from her lessons, God had promised He would never destroy the world with a flood again and He’d given the rainbow as a sign of His promise.

It seemed as if God had changed His mind.

Tamara turned from the window and found her grandfather’s pack of cigarettes on his desk and the matches in the top drawer where he kept his fancy pens and stationary. She didn’t light a cigarette, but she did light the candles she’d found in the top drawer. The sight of the candles on the desk gave her an idea. She started digging through the drawers. If God destroyed by water, she would destroy by fire. Tonight she wanted to destroy everything. Business papers. Letters. Her grandfather’s Last Will and Testament if she could find it so she wouldn’t inherit anything because she didn’t want it. She didn’t want a brick of this place. She didn’t want a dime. In a drawer she found a handgun and bullets. Granddaddy’s revolver her mother had threatened to use to shoot Kermit. Tamara opened the window and held the gun out over the water. Except...no. What if she needed that later? She closed the window, kept the gun. The police might come for her. She wouldn’t let them put her in jail for what she did. She’d rather die first than take the blame. Her mother had set her up, left her alone so her grandfather could have his way with her. Her mother would burn for this, too.

Tamara dug every sheet of paper out of the drawers. She tossed his ledger books into the wire wastebasket, an appointment book, anything she could get her hands on. Anything she could burn, she would burn.

Papers weren’t enough. Accounts weren’t enough. She wanted to burn the very heart of Red Thread. The bottle. The first bottle and Veritas’s red ribbon. Where was the bottle?

She picked up a candle and walked around the room, looking along the walls, across the tables. In the corner of the room she saw a girl holding a candle. H

er. Her reflection in the glass front of Granddaddy’s liquor cabinet. She raised the candle to the cabinet and peered inside, spying row upon row of amber-colored bottles tied at the neck with a red ribbon. The glass bottles danced with the light of her candle flame, and for a moment it appeared they all held fire inside them. Tamara set her candle down, wrapped the pink blanket around her arm and with her elbow smashed in the glass.

Tamara dropped the blanket on the floor and stood on it out of the way of the broken glass. She’d been hurt enough tonight. Red Thread wasn’t ever going to hurt her again. She dug through the cabinet looking at every bottle by candlelight. One bottle was from this year. Another from 1970. Another bottle was old enough its ribbon had faded to a dull pink, but it wasn’t old enough to be the bottle she sought.

Then she saw it.

In the very back of the cabinet on the bottom shelf in a glass box all its own was the bottle. The first bottle. She pulled out the box and slid the glass lid off the top. From a nest of red velvet, she lifted the bottle out. Around the neck hung a limp and ratty ribbon, rust-colored with age. She set it on the counter, smiling. She didn’t know what she should do with it. Drink it? Pour it into the river water? So many choices, each one better than the last. She had to think of something good, something that would hurt Granddaddy and Jacob Maddox even in their graves.

Tamara would wait, think it over. In the meantime, she should hide the bottle again. She went to put it back in its velvet bed and noticed something else in the box with the bottle—an envelope. An envelope her grandfather had hidden.

She pulled it out and examined the front. The handwriting...she knew this handwriting.

Her father... Daddy.

He’d written this letter. It was addressed to her grandfather. She kissed the words on the paper because she missed him so much. Tamara took the letter, took her candle and walked to the desk chair, where she sat to read it, the bottle long forgotten.

Dad,

By the time you receive this letter, I’ll be dead. I can’t stay on this earth another day. Every single day of my life has been a lie. I do not love my wife. I have never loved my wife. I have never loved any woman and never will. It is my greatest regret that I chose your money over my soul and allowed Virginia to be trapped in this prison of a marriage with me.

You can have your money. If you’ve seen my soul anywhere, I’d like to have it back.

I am not taking my life to punish you so much as to free Virginia from this farce of a marriage and from the Maddox family. I fear she will make the same choice I did, taking your money and selling her soul, but I will die with a clear conscience knowing I have at least tried to free her. I’m tired of pretending that Tamara is my daughter. Even Virginia is tired of pretending. Did you know she told me that Tamara was Daniel Headley’s daughter, conceived at Eric’s going-away party? I laughed when she told me. Virginia is more a Maddox than I am. You’ve taught her well.

You should know... I love Tamara as if she is my daughter, and my last wish for her is that my death will free her and Virginia both. Let them go, Dad.

It is not easy for me to die knowing what I know about Levi Shelby. I know you’ve had your affairs, but I never dreamed you’d stoop so low to seduce a cleaning lady who couldn’t tell you no any more than the rest of us could. Levi seems like a good young man. I assume he’s turned out so well because he was raised outside this family and without the taint of the Maddox name and the poison that is in every bottle of Red Thread. I hope he never knows who he really is, for his sake. But considering he is the only son you have left, I know his days as a man free and happy are numbered. But better him than my Tamara as your heir. Our family is cursed, they say. I will testify to that. I will be at peace only when I am no longer a part of it. Virginia recently said to me that over her dead body will she allow you to leave a single cent of our family’s money to Levi. Feel free to leave every cent of it to him over my dead body instead.

Do not consider my death as you losing another son.

Consider it you losing everything.

I go to join my beloved Eric now, my brother and my friend. He knew what I was and who I was and loved me in spite of it all. I have missed him. It will be good to see my brother again.

Your son,

Nash

Tamara folded up the letter and slipped it back in the envelope.

One by one she pulled the papers out of the trash can, the books and the ledgers. She didn’t burn a single thing.

Instead, she went into her mother’s bedroom and took off her clothes, all of them. She opened the window and saw the river under the bottom sill. The cold air wrapped around her naked body and she felt clean again. She threw her soiled pajamas into the black night water along with the hateful pink housecoat. They floated away—good riddance. When she looked down into the water, she saw her reflection twisting and stretching. The face wasn’t her face anymore, but another girl’s face. And that girl was in the dark water with a red ribbon tied around her hair. It couldn’t be her... Tamara wasn’t wearing a red ribbon in her hair. Where had it come from?

She raised her hand to her hair. No ribbon. She looked at her fingers and saw they’d turned red. Blood. She was bleeding from a cut on her head. That was all. She must have cut herself with the glass from the lamp while fighting with Granddaddy. She laughed at herself for thinking she was someone she wasn’t. Silly girl. She closed the window and dressed in her mother’s clothes and wrapped herself in her mother’s blanket, which smelled of bourbon and cigar smoke.

She went back to Granddaddy’s office and pulled a chair to the window. In the distance through the trees she could see flickering lights—flashlights or headlights or both. Someone was alive out there. Someone would find her eventually.

But it didn’t matter anymore that someone find her. She’d found herself in her daddy’s letter. But not her daddy at all.

“I am not a Maddox,” she whispered. The ecstasy of the knowledge smoldered inside her, glowed, burned. She’d never spoken five more beautiful words in her life. She didn’t have Maddox blood in her veins, that vile blood that had raped Veritas, that had sold her and her baby. She wasn’t one of them. She wasn’t cursed. And that was why she’d lived and Granddaddy had died. The curse had struck him and spared her. Because she wasn’t a Maddox. She wasn’t a Maddox at all.

But Levi was. And yet he hadn’t been good enough for her grandfather. He’d wanted a white son, all white, and she’d been the chosen vessel for the chosen boy. A ripe teenage girl under his own roof. No wonder he had made her and Momma move in with him. No wonder.

Tamara smiled. She had an idea. Her mother had said she would let Granddaddy give a penny of Red Thread to Levi over her dead body.

Her mother hadn’t said anything about her live body.

More tired than she’d ever been in her life, Tamara closed her eyes and snuggled deep into the blanket to rest. She’d need all her strength to make it through the next few weeks. The water had stopped rising. She would survive this night. When the police came, she would tell them this story—that her grandfather had been drinking and she’d gone upstairs to sleep. Why upstairs? She’d need an answer for that. She’d gone upstairs to sleep because she wanted to sleep in her mother’s room so she’d know when Momma came home. There. They’d fought and Tamara wanted to apologize, so she waited upstairs on her mother’s bed. She’d fallen asleep and then woke up when the lights went out. She’d gone downstairs to check things out and found the house full of water and Granddaddy floating there facedown. It was too late. He’d drunk so much he’d passed out, and he’d drowned in the flood. What could she do except go back upstairs and wait to be rescued? She’d broken the glass of the liquor cabinet because she tripped in the dark. She had an answer for every question they’d ask. For now, for tonight, she was safe and she was free. And tomorrow she’d start figuring out how to shoot Granddaddy’s gun.

Although she’d had only a sip or two of Red Thread, Tamara felt dr

unk and happy. Happy because she was alive, yes. Happy because she wasn’t a Maddox, indeed. But happiest most of all for one very good reason.

Tamara Maddox had a plan.

8

Paris

“You were right,” McQueen said. “Maybe I don’t want to hear this story, after all.”

“Too late. The train has left the station. No stopping it until the end of the line.” Paris crossed her legs, long beautiful legs. He didn’t even want to look at them anymore. Nor her face, either. But she looked at him, stared at him. Her face was a sealed bottle, corked and capped and covered in foil. He could get nothing out of it.

“Tamara tied the red ribbon around her grandfather’s finger,” he finally said. “Smart.”

“You’re familiar with the tradition?” she asked, seeming pleased with him.

“I don’t know where it started,” he admitted. “But they said Red Thread drinkers would take the ribbon off the neck of the bottle and twist it around their fingers if they managed the manly feat of drinking an entire bottle in one night. A badge of honor.”

“A badge of dishonor,” she said, scoffing. “Drinking an entire bottle of bourbon in one night? That’s something to be proud of? Makes as much sense as keeping the panties from the prostitute you paid to lay you. Where’s the glory in that?”

McQueen laughed, but it didn’t feel right, laughing after hearing that story.

“Depends on the prostitute, I guess,” he said. “I know those old bottles. They aren’t that hard to drink in one long night. What? Ten shots? Twelve?”

“George Maddox had a nickname in certain Kentucky circles. They called him ‘The Baron.’ The good ole boys called him that. He called himself that. One of the last great bourbon barons. He took his title seriously. That man could polish off a full bottle of Red Thread in a night. And then he’d take that little red ribbon off, put it on his finger and wear it into the office the next day. Big man. He liked to show that he could hold his liquor. It was a point of family pride.”

“He has a pretty sick definition of pride. Raping his own granddaughter. Even if Tamara wasn’t his granddaughter—”

“She wasn’t his granddaughter, no, but the whole world thought she was. Any baby she had would be a Maddox in the eyes of the world—even more important, in the eyes of George Maddox.”

“But still...he raised her like a granddaughter. And he did that to her? Really?”

“He did what I said he did.” Paris gave him a look that said Doubting Thomases will not be treated kindly. “George Maddox was a

The Bourbon Thief

The Bourbon Thief The Saint

The Saint The Siren

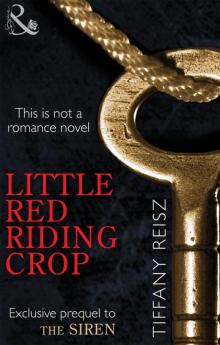

The Siren Little Red Riding Crop

Little Red Riding Crop Her Halloween Treat

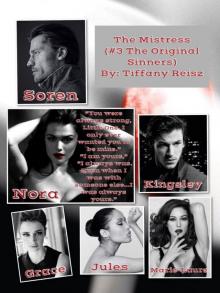

Her Halloween Treat The Mistress

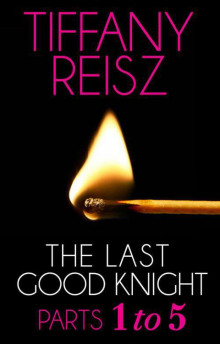

The Mistress The Last Good Knight

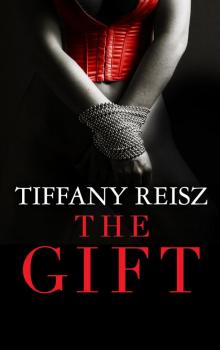

The Last Good Knight The Gift (Seven Day Loan)

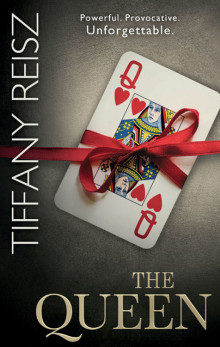

The Gift (Seven Day Loan) The Queen

The Queen The Angel

The Angel The Prince

The Prince Misbehaving

Misbehaving The Red

The Red Submit to Desire

Submit to Desire The Priest: An Original Sinners Novel

The Priest: An Original Sinners Novel The Lucky Ones

The Lucky Ones The Mistress Files

The Mistress Files Mischief

Mischief The King

The King The Night Mark

The Night Mark The Virgin

The Virgin Her Naughty Holiday

Her Naughty Holiday One Hot December

One Hot December The Auction (The Original Sinners Pulp Library)

The Auction (The Original Sinners Pulp Library) A Winter Symphony: A Christmas Novella

A Winter Symphony: A Christmas Novella The Pearl (The Godwicks)

The Pearl (The Godwicks) Immersed In Pleasure/Submit To Desire (The Original Sinners Pulp Library)

Immersed In Pleasure/Submit To Desire (The Original Sinners Pulp Library) The Rose

The Rose Winter Tales: An Original Sinners Christmas Anthology

Winter Tales: An Original Sinners Christmas Anthology Winter Tales

Winter Tales The Last Good Knight (The Original Sinners Pulp Library)

The Last Good Knight (The Original Sinners Pulp Library) The Return (The Original Sinners)

The Return (The Original Sinners) 0778318435 (A)

0778318435 (A) Seven Day Loan

Seven Day Loan Picture Perfect Cowboy

Picture Perfect Cowboy The Christmas Truce

The Christmas Truce 10 Shades of Seduction

10 Shades of Seduction The Chateau_An Erotic Thriller

The Chateau_An Erotic Thriller The Christmas Truce: An Original Sinners Novella

The Christmas Truce: An Original Sinners Novella Immersed in Pleasure

Immersed in Pleasure Harlequin E Shivers Box Set Volume 4: The HeadmasterDarkness UnchainedForget Me NotQueen of Stone

Harlequin E Shivers Box Set Volume 4: The HeadmasterDarkness UnchainedForget Me NotQueen of Stone Something Nice: An Original Sinners Novella

Something Nice: An Original Sinners Novella The Confessions

The Confessions The Mistress Files: The Case of the Acting ActressThe Case of the Diffident DomThe Case of the Reluctant Rock StarThe Case of the Secret SwitchThe Case of the Brokenhearted Bartender

The Mistress Files: The Case of the Acting ActressThe Case of the Diffident DomThe Case of the Reluctant Rock StarThe Case of the Secret SwitchThe Case of the Brokenhearted Bartender One Hot December (Mills & Boon Blaze) (Men at Work, Book 3)

One Hot December (Mills & Boon Blaze) (Men at Work, Book 3) The Scent of Winter: A Novella

The Scent of Winter: A Novella Little Red Riding Crop (Spice) (Prequel to The Siren: Book 1 in The Original Sinners series)

Little Red Riding Crop (Spice) (Prequel to The Siren: Book 1 in The Original Sinners series)